The haul trucks are no longer visible in the Minorca Mine open pit, where the road bends between Biwabik and Gilbert. Only warming temperatures would erase the snow from an early April blizzard. Not the movement of the Iron Range economy that was on display nearly every day along Highway 135.

It was a cruel bit of irony, that snowstorm. It blew in as Minorca workers were winterizing the taconite mine, pulling the pumps from its cavernous pits and bracing themselves for a familiar uncertainty. Being on the wrong side of a mining economy’s cyclical nature is as much part of the Range way of life as the generations of families that passed their hard hats down to the next.

There’s always hints when a downturn is on the horizon.

They arrived a month earlier when Cleveland-Cliffs spelled out $700 million in losses in 2024, and more than $430 million in the fourth quarter alone. Auto sales shrunk. Mining operations that ran full bore throughout the year meant a stockpile of pellets. The writing was on the wall, but the news still stunned the region when Cliffs announced it would idle Minorca and cut production at Hibbing Taconite, laying off 630 workers

Only days before, the Range celebrated as one of its storied hockey programs reached the state tournament, providing a viral moment and showcasing the beloved flow of “hockey hair” along the way.

The good vibes would turn gloomy in a week’s time.

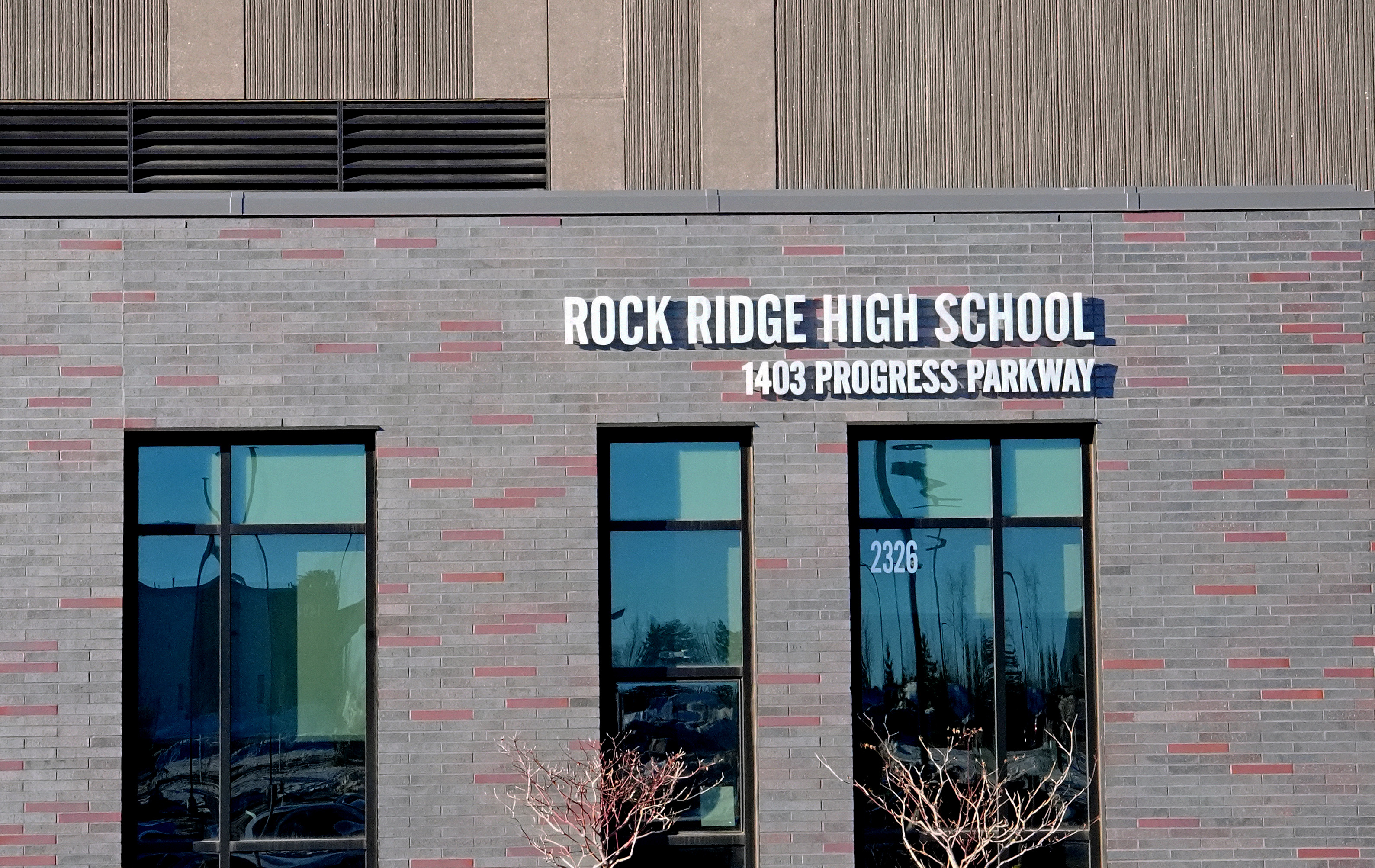

Rock Ridge and Hibbing school districts were busy addressing millions of dollars in budget deficits, putting dozens more jobs on the chopping block. Justin Eichorn, a state senator representing the region, was jailed and federally charged with soliciting a minor for prostitution. At Rock Ridge High School, which encompasses the cities of Virginia, Eveleth and Gilbert, its dean of students was arrested on child exploitation charges and extradited to Georgia.

Cliffs announced its layoffs, the senator resigned hours later, and it was only Thursday.

This turn on the down cycle wasn’t the same old ride.

“It does feel different,” said Rob Farnsworth, a state senator from Hibbing. “It feels like the Iron Range is a boxer on the ropes, and we just keep taking punches.”

It would be an understatement to say the last month has hit close to home for him. Farnsworth grew up on the Iron Range in the 1980s, when mine closures decimated the workforce and economy. His district represents five of the six active mines — including Minorca and Hibbing Taconite — and two potential new ones.

It also covers Rock Ridge and Hibbing schools, among several others bogged down with statewide budget shortfalls.

Farnsworth is a special education evaluator by trade in his home district, where a number of staff in his department were among cuts at the school. The senator takes leave from the school district during the legislative session, and he’s among the longest-tenured teachers, so his own job wasn’t unusually in jeopardy.

But the dual threat of mining and education job losses has been at every turn. As a legislator, he’s tasked with figuring out the problem. At home, it’s more personal.

“I have friends at the school I know won’t be back next year, and I have friends at HibTac and Minorca who might not have a job,” Farnsworth said. “I don’t really look at the difference between them. This is the job I signed up for and I have to plow through for them.”

A fragile foundation takes more hits

So much of the Iron Range economy revolves around the mining industry that the sense of urgency has never touched education job cuts in the same way.

Among the top tourist attractions in the region are mine overlooks and historic places. A mountain bike park was shaped through an old mine site. The Mesabi Trail winds alongside the red-rocked open pits. The area’s top-rated golf course sits on reclaimed mine land. The list goes on.

Entire communities have moved locations, houses and all, when mines expanded in the early days. Highways are still moved and towns reshaped for the same reason, as not to disrupt the corporations that keep people employed and the lights on.

At the end of the day, only a third of the miners come home and return the next than did so in the late 1970s. They make up just 5% of jobs in northeastern Minnesota (excluding Duluth), but are the highest paid at more than double the annual average wage — a gap of $116,233 to $52,911 — according to the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED).

Education is the fourth largest employer in the region at 8.5% of jobs, with an average annual wage of $49,329. Administrators and top-end union teachers can close in on or surpass $100,000 annually. When coupled with mining layoffs, retirements and administration cuts mean more of the highest earners are pulling back from the local economy.

“It’s true that a teacher makes less than a miner, but it’s still a breadwinner salary that a lot of families depend upon,” said Aaron Brown, a local author and columnist for the Minnesota Star Tribune Editorial Board. “Like miners, people who lose these jobs will only consider jobs that are comparable in salary and will leave the area if they can’t find one. That means that these layoffs, which will number in the hundreds across the region, matter as much as mining layoffs.”

Iron Range schools aren’t alone in slashing their budgets. There’s a $280 million shortfall for 47 metro schools for the 2025-26 year, placing pressure on superintendents in rural districts and the Twin Cities alike. Though rural areas are historically more likely to take on the long-term population impacts.

“Education cuts, in general, become a structural defect in the community,” Brown added. “It won’t fall apart right now. But it will later, unless we care about restoring our framework.”

Underscoring this is the makeup of the Range economy.

The region’s second and third largest employer industries are retail (13.8%) and accommodation/food services (10.7%), per DEED data. Both have wages well-below the average, and traditionally are among the first non-mining businesses to suffer in prolonged downturns. Thirty percent of households make $100,000 or more annually, while 26% don’t even clear $35,000 a year.

Those figures all represent the diminished options for the other half of the population, the Iron Range middle class, when jobs disappear or new opportunities are sought.

Diversifying is an arduous process, both practically and culturally.

Rangers have leaned on new mining prospects — copper-nickel proposals at Twin Metals, NewRange and Talon Metals — to bring in high-wage job growth and provide current miners a landing spot at home. Other efforts, like a wood siding plant and capitalizing on the potential cannabis industry, have either failed to come to fruition or are in their infancy stages.

The scars from this and the 1980s downturn are visible in the region’s historic population trends and projections.

Zooming in, St. Louis County lost 11% of its residents in the 1990 Census that measured the previous decade, according to the Center for Rural Policy and Development (CRPD). By 2020 it increased to 1% above the post-downturn count. Most of the Iron Range cities, notably Virginia and Hibbing, have seen total population losses of about 25% from 1990 to today.

Birth rates are outpaced by death rates statewide, and by 2050, the CRPD projects St. Louis County will lose 11% of its 1990 population.

“I see a lot of ghost towns up in northeastern Minnesota because people are leaving,” said Cathy Chavers, the former chairperson of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa. “There’s no jobs, no housing.”

Uncertainty rules the day

More than a month has passed since the bottom fell out from the Iron Range, and like a mine pit after a windstorm, the dust is still settling.

Al King was not a year into his role as president of the United Steelworkers (USW) Local 6115 at Minorca, when the layoff notices arrived. Still fresh-faced, it wasn’t his first go-around in the process of idling a mine, but it was at odds with previous times.

Minorca last idled in 2009. It was spared during the most recent mass downturn in 2015. King heard the signs from Cliffs CEO Lourenco Goncalves, who referenced in the company’s year-end call a decision to keep two facilities running at full production in 2024. The 340-plus layoff notices made clear that comment directly referenced Minorca.

Cliffs officials told King they had 4 million tons of excess pellets with no place to put them. Clearing the overstock could take up to six months. The company would later slow operations at a plant in Michigan due to slumping auto sales, though Cliffs has been bullish on tariffs boosting the industry.

Like nearly every other downturn, economic trends will dictate Minorca’s return. But with the economy on shaky grounds and steel tariffs in flux, the indicators of a short idle period aren’t showing up yet. U.S. Steel, on Monday, reported $116 million in losses during the first quarter of 2025. It’s mired in its own uncertainty over a potential sale to Japan’s Nippon Steel.

The distinction from other idles is in the details. Unlike 2009, there will be no maintenance projects or the usual housecleaning items at Minorca. Cliffs wanted the mine winterized — and fast. Production would stop, equipment pulled out and a small crew numbered in the teens was to remain on fire watch.

It’s a plan for the long haul.

“This could only be the beginning of what we’re looking at,” King said in a video posted on YouTube. “And I know it’s somewhat grim, but it is somewhat the reality … The Iron Range is in a position where it could get worse before it gets better.”

The question at Hibbing Taconite was if, not when, all 240 miners would return. Where Minorca has a healthy supply of ore reserves, HibTac has been running out of minerals to unearth. By halving its workforce and minimizing production, it’s possible for Cliffs to extend the mine’s life by eight years.

Chris Johnson, president of USW Local 2705, knew there wouldn’t be any clear answers to the question of what HibTac would look like in the coming years.

He’s worked with the company and local politicians for more than a decade to keep HibTac open beyond its current 2026 reserves projection. Reducing production buys valuable time, but it doesn’t guarantee legal battles and plans around other mineral leases will resolve. Or that people can ride it out in the long run.

“We are treating this as permanent,” he told a Minnesota House committee.

On the schools side, there’s equal uncertainty. Hibbing slashed 21 positions in early April to address $1.8 million of a $2.8 million total budget shortfall. Days later Rock Ridge approved cutting 13 teachers, 20 paraprofessionals and eight other positions, among other items, to reduce its budget by $2.4 million.

Declining enrollment and inflation costs, married with a lagging state funding formula, contributed to school districts struggling to stay above water. Minnesota approved more than $2 billion in K-12 education funding in 2023 that included a boost to the per pupil formula, but a number of mandates restrained how far the increase could be spread.

Now state lawmakers are navigating a budget year with a projected $6 billion deficit and unknowns at the federal level. Reduced production from the mining industry will deliver impacts to the school trust fund. Same for the districts serviced by the Department of Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation (IRRR), which collects a production tax over property tax and distributes it around northeastern Minnesota schools on a three-year rolling average.

“We have to keep that in mind as we’re moving forward,” said Andrea Lintula, business manager at Rock Ridge. “It’s a very big thing in our community. Always something to keep in the front of our mind.”

For laid off miners and teachers, the options are limited

A bill to extend unemployment benefits to miners passed through the Minnesota Senate this week. It has a clear path to Gov. Tim Walz’s desk and would keep benefits active beyond Christmas.

Nobody knows how long this will last for Minorca or Hibbing Taconite. Stretching out unemployment buys time, if nothing else, to help Steelworkers “hang in there” as King said. Like steel tariffs, it’s only a short-term solution.

Mining jobs on the Iron Range decreased from more than 12,000 in the 1980s, to below 4,000 in 2023. Beyond a few openings here and there, current mines can’t absorb hundreds of workers back in the job hunt.

Transfer and movement options have entered the discussion, be it closer to home at Northshore or Tilden Mine in Michigan. Steel mill jobs in Indiana and Ohio could open up down the road. Steelworker facilities outside mining, namely a manufacturer in International Falls, are being circulated as it looks for millwrights, electricians, laborers and more.

Eighty-one Hibbing Taconite employees took voluntary six-month layoffs with callback rights, reducing the likelihood they will seek transfers. Still, with few soft landing spots close to home, the realities are setting in.

“If some of you were on the fence thinking it’s totally hopeless, that’s not the case,” King said. “I know moving to Michigan is a big endeavor, but it’s an option for you.”

Teachers also have few options. Enrollment projections show further declines, the status quo, or only small gains across local districts over the next decade.

Rock Ridge has gone through this process the last four years, cutting more than 40 teachers, but bringing a number of them back as the budget settled. This was the case last year when the board replaced more than $1 million in across-the-board cuts. Doing so again is unlikely in the cards, even if legislators work out more funding for schools.

“The correct answer is ‘No,’” said Director Tim Riordan this week.

For the Range, the twofold job losses help spin a vicious cycle. As jobs go away and people leave, the mechanisms of union contracts reduce positions from the bottom up of seniority. That means younger professionals at mines and schools are at greater risk of not returning or moving to different regions and states.

CRPD migration rates show St. Louis County lost about 26% of its population who would be aged 25-29 between 2000 and 2010, and 27% aged 30-34. The county attracts a large number of 20-24 year olds due to the universities around Duluth, said Kelly Asche, a senior researcher for the CRPD. They just don’t stay.

In the same vein, St. Louis County is better at attracting and retaining 35-49 year olds. But that 25-34 age range is generally when families are built and roots put down in a community.

“If you’re upset about mining jobs, you should be just as upset about teacher jobs — and delivery driver jobs, manufacturing jobs and any other jobs we might be losing right now,” Brown said. “Anything that sends young professionals and families away from the Range is bad.”

‘A lot of years of potential left’

Farnsworth, the Hibbing state senator, has been through enough downturns and idles to see a light at the end of the tunnel. What the Iron Range looks like in six months might be different when it comes out the other side, but the drum beat of resiliency continues.

Uncertainty be damned.

He can play a direct role in the Range’s future as a legislator and chair of the IRRR Advisory Board. To him, it’s all about economic development and supporting the mining industry beyond the finite taconite reserves.

Scram mining can take waste rock and extract metal out of them, just not to the same employment and economic level as current mining operations. Farnsworth co-sponsored a bill with Range Delegation members to address the state’s sulfate standard, which poses an expensive hurdle for active mines going through repermitting.

Environmental groups are also pushing regulators for a new review on Mesabi Metallics, a potential new taconite mine and processing plant in Nashwauk.

“We have to make it possible for the new mines to open,” he said. “We have to do what we’re able to do to make sure the rest of the mines remain viable.”

Diversification always comes to the forefront during a mining idle. It’s not for a lack of trying, but large-scale projects promising hundreds of jobs have left the Range high and dry. The environmental review process has pushed some companies to other locations, or to split their project sites between neighboring states.

Yet, the solar panel industry has expanded on the Range and across Minnesota in recent years. Two cannabis projects are looking to open in Itasca County. The IRRR approved a $2.5 million loan for a startup cannabis business west of Duluth, and a cannabis dispensary opened this year at Fortune Bay near Tower.

Farnsworth is looking to lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic as the next step for the Iron Range. Remote work caught on and stuck for many private industry employers — though some companies and the state have started requiring a return to in-office work — and rural areas benefited the most.

The CRPD’s annual State of Rural report in 2025 showed in-migration rates from Minnesota favored rural counties, which experienced modestly higher population rates in 2023 compared to 2020. It’s been a trend since the 2010s, mainly coming from urban counties and people seeking more affordable housing in the so-called lakes region.

That’s an attraction point for parts of the Iron Range region, Farnsworth said, and an opportunity. He envisioned building hundreds of affordable homes under $300,000 from Grand Rapids to Aurora, equipped with high speed internet, and letting the natural draws of lake life, less traffic and rural charms to lure metro-based remote workers.

In theory, it’s a simplistic equation for the region: More people to fill job vacancies, more families to boost school enrollment and — ideally — less impact to the broader communities when the next downturn comes.

“We’ve been through worse and we’ll get through this,” he said. “The Iron Range has a lot of years of potential left.”