In a snapshot, nothing about this moment seems out of place.

It’s a casual Wednesday evening in Virginia, a few days after the start of school. The local cross country team holds a meeting in the grass outside the Iron Trail Motors Event Center. Cool, 50-degree temperatures supply a longing for the coming fall months.

Step into that snapshot, and the vibe changes.

Hundreds of people are pouring into the building, crowding the hallway and open spaces. Some are tracking down speakers and monitoring the time. Others are simply trying to find a spot out of the way.

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) will soon open a public hearing on permit renewals and a variance request for Keetac, the taconite mine located about 30 miles west. Later, the meeting will pause as event staff open up a wall to add more seating for the nearly 500 people in attendance.

If the state’s application of its sulfate standard seems like a sleepy enough issue, this night would prove otherwise. On the heels of one mine being fully idled, and another’s workforce halved, Iron Rangers have grieved, fretted, revisited past traumas and settled into a familiar pattern. There’s still something to fight for, so here they are.

The moment is controlled chaos.

It’s urgent. Contentious even. It’s the latest intersection of Minnesota’s policies, industry economics, environmental protection and jobs. This time over taconite mines, but with the same undertones of politics, leadership and globalized markets.

****

“This is the perfect storm,” said John Arbogast, a District 11 United Steelworkers (USW) representative, 30-year industry veteran and former president of USW Local 1938. “Yeah, right now, it’s a Keetac issue. It’s bigger than that.

Arbogast is one of those go-to pillars in the region, and he’s among only a few left. He’s direct from central casting for a union leader, with a penchant to speak his mind. Sometimes, he’ll tell an audience he’s trying to behave during his remarks. It’s his most endearing trait on the Iron Range. How he embodies a place that treasures big personalities.

When Arbogast is the one worried about outcomes, it should hit differently. He’s pretty much seen it all.

A 1984 graduate of Virginia, his most formative years were during the Range’s prolific downturn, from which it never truly recovered. When friends lost their jobs during the 2000 LTV shutdown, many joined him at Minntac. He was in the room with President Barack Obama’s chief of staff in 2015, advocating for solutions after dumped foreign steel idled nearly every mine.

Iron Rangers live in a fluctuating state of existential crisis over their primary industry. When things are business as usual, there’s a certainty in the flow of everyday life. In the nightmarish lows, the mood is something similar to a quiet panic, in which they control almost nothing.

What’s the future hold? That might be up to a corporate board room, the state of the steel market or the whims of an executive.

The backstory of every mine idling reads like it’s from Charles Dickens, where ghosts of closures past haunt the Range, which then has to look at its present and question its future. In this case, it’s Bob Cratchit, not Scrooge visited by the specters.

Arbogast can lay out the worst-case scenario, where the MPCA enforces the sulfate standard, a rarely-if-ever-enforced rule since it was created in 1973. It will require nearly $1 billion of investment for Keetac to comply. It’s possible the mine simply closes. Minntac is next up for permitting. Then United Taconite.

A systematic closure of the Iron Range taconite industry seems a little doomsday, yes, but it’s not inconceivable to those bearing old scars.

“What are we gonna do on the Iron Range?” Arbogast asks. “When times are tough, they’ll make decisions, and U.S. Steel will make a f***ing decision to idle Keetac.”

****

When Paula Maccabee first answers the phone, her question is humorous in one sense, but makes clear she understands there’s animosity between her and the mining crowd. “Are you calling to ask why my face is on dart boards across the Iron Range?”

Maccabee is the executive director and legal counsel for Water Legacy, a Duluth-based environmental group best known for its opposition to copper-nickel mining in northeastern Minnesota. It’s been in the sulfate standard mix from the start, and most recently filed a lawsuit against a tailings basin expansion at Northshore Mining.

Maccabee is a graduate of Yale Law School. Her resume spans work in private practice, as a public interest lawyer, a stint with the Minnesota Attorney General’s office, and four years as a city councilor in St. Paul. She holds a fourth-degree black belt in taekwondo. Few are more prepared than Maccabee to walk into a room full of Iron Rangers and challenge the mining industry.

When she has, Water Legacy has found success with the courts, winning lawsuits against state regulators and copper-nickel companies that have forced once-approved permits back into review. Some of the industry’s strongest advocates for permitting reform want to effectively remove the judicial branch from the process, an apparent effort to neutralize environmental groups. That’s how formidable she’s been.

There’s precedent in Minnesota, Maccabee says, for how the sulfate standard is playing out. In the 1970s, the state’s northern lakes were among those heavily impacted by the acid rain phenomenon. Minnesota was ahead of the national curve to pass environmental legislation in the 80s, and Congress followed in the early 90s.

The debate over industrial regulation was similar. Treatment solutions were implemented and more cost-effective ways emerged over time. Maccabee says this is the history to draw from today. Governments realized the risk, enforced new regulations, and corporations dug into the profit margins to manage pollution.

Acid rain isn’t an issue now. The price of preventing it is known and accepted as a cost of doing business.

“What we can do as a community is say we want companies to control their pollution, period,” she said. “We will support the government when they require that, and we will not support the government if they put their hands over their eyes. Sometimes that might mean having to go to court.”

****

If there’s one thing environmental groups and the mining industry could possibly agree on, it’s that policies in Minnesota can be inconsistent. They have different goals, to be sure, which is how regulators can tie themselves into knots trying to balance opposing interests.

A 2024 survey of mining companies conducted by the Fraser Institute ranks the investment attractiveness of mining jurisdictions around the world, broadly measuring a place’s mineral practices and policy perceptions. Out of 82 locations, Minnesota ranked in the bottom 10 at 72nd overall, and 69th when looking only at policy.

Digging deeper, the state was no better than seventh-worst in categories of interpretation and enforcement of existing regulations, uncertainty concerning environmental regulations, and regulatory duplication and inconsistencies.

Setting aside the statistical significance of the survey — Minnesota received between five and nine responses from the 350 total respondents — it matches the anecdotes of mining companies housed on the Iron Range.

The sulfate standard may well be the poster child.

It was enacted in 1973 and based on 1940s research. In the decades since, there’s been little to no enforcement. The science, if it’s generously dated to 1949, is a year shy (76) of the average life expectancy for Americans (77). Efforts to revise it have been denied, or dropped altogether.

“We’ve kind of had moving goal posts throughout this whole thing,” said Chrissy Bartovich, environmental director at U.S. Steel’s Minnesota Ore Operations. The company had applied for a site-specific standard for Keetac in 2022 and was told to provide data about wild rice growth in nearby Hay Lake.

In 2023, she added, the state asked for 10 consecutive years of statistics. U.S. Steel couldn’t meet the request. “Even though we have data that shows it’s growing, and it’s healthy, it doesn’t matter because every time we come up with something new, the rules change.”

Thousands of water formations across Minnesota are noted by regulators as containing wild rice. In 2008, the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) submitted a widely-cited report to the Legislature on natural wild rice growth, but provided no data on Hay Lake’s acreage or wild rice levels contained within it.

In 2010, and again in 2018, the DNR published its list of the most important wild rice waters in Minnesota. Hay Lake was absent. It was flagged on the MPCA’s impaired waters list, but the state’s public data on wild rice growth trends on Hay Lake appears scarce, or nonexistant.

“When the MPCA reviewed the site-specific standard that U.S. Steel provided, they provided limited data for us to understand how much the wild rice is, and whether it’s self-sustaining,” said Paul Pestano, a water assesssment manager at the agency. “So we welcome any information that will help us better understand and evaluate that.”

Minnesota’s recent work on the wild rice sulfate standard dates back to 2011. Under former Gov. Mark Dayton, regulators were tasked by the Legislature to study and revise it, thus slowing implementation and compliance schedules.

Environmental groups pushed back, and in 2018, an administrative law judge rejected the work of the MPCA, leaving the 1973 rule in place.

“When our state is not strong enough, or courageous enough, to follow our own rules, it creates problems,” Maccabee said. “The best way to solve them is just to say, ‘Time’s up, guys. We’re following our rules, and so are you.’”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) would ultimately send the state a letter in 2022 directing it to start enforcing the standard, and that measures passed since 2011 remained out of compliance with federal law. It also urged the MPCA to work with the Legislature toward a resolution.

“Right now, we are in a situation where regulatory agencies are not currently collaborating with the Legislature to resolve this issue,” said Paul Peltier, executive director for the Range Association of Municipalities and Schools (RAMS). “That’s a missed opportunity. An opportunity where people can pick it up and move it forward. What is the appetite to do so?”

****

In St. Paul, the life of the sulfate standard has spanned eight governors. Among them four Democrats, three Republicans and one Independent. It went into effect under Wendell Anderson, and Dayton would put into motion the 2011 review that led to today under Gov. Tim Walz.

Dayton’s two terms marked the high point for efforts around the standard, and highlighted the political lanes he had to straddle. He signed laws around wild rice and sulfates in 2011, 2015 and 2016, vetoing a 2018 law that tried to outright abolish the rule, while former Minnesota Attorney General Lori Swanson called it “imprudent” to enforce.

Still, following the administrative law judge’s decision, Dayton convened a task force to look further at wild rice and sulfates. It consisted of mining and tribal officials, as well as experts, community representatives and more. Collaboration, he would say, was necessary.

Among the task force’s recommendations, delivered in the final days of his administration, was to create a permanent wild rice stewardship council to oversee monitoring, restoration and regulation, among other duties. It also called for more clarity on variances granted around the sulfate standard.

“Nothing happened,” said Bartovich, a task force member. “None of those were acted on because it was a change in administration.”

What shifted over the last seven years in St. Paul’s approach to the sulfate standard is most easily explained as stylistic differences between Dayton and Walz.

The former was hands-on with matters of mining, for better or worse, depending on the issue and what side he was on. Dayton strongly supported the NewRange (formerly PolyMet) project, but was among the most vocal elected officials opposing Twin Metals.

Walz, on the other hand, has tended to lean on his agencies and the process. That’s upset environmental groups around copper-nickel mining, and equally so Iron Rangers when the courts have kicked permits back to the agencies.

Arbogast and Bartovich said the administration deserved credit for fast-tracking Keetac’s direct-reduced iron (DRI) facility, but questioned if more direct invention from Walz would have meaningfully advanced the sulfate standard conversation one way or another.

“That’s what we’ve seen in other jurisdictions,” Bartovich said. “When you have a governor that directs the commissioner to fix your permitting problem, fix this rule, and it’s very direct and he says to get it done, they get it done.”

Local officials told Iron Range Today they spoke with Walz last month about the sulfate standard, specifically around the 2022 EPA letter, if federal regulators would withdraw it and the potential downstream effects of doing so. Their brief discussion left them feeling optimistic.

The governor’s office did not respond to questions from Iron Range Today about how a rescinded letter would impact current sulfate standard processes, or if Walz supports its revocation.

Even if he does, the political climate being what it is — and especially after the governor’s vice presidential bid — it’s unlikely he would find a helping hand in the Trump administration to move it forward.

Kesley Emmer, a spokesperson for Republican U.S. Rep. Pete Stauber, said the congressman spoke to EPA Region 5 Administrator Anne Vogel this summer about the MPCA updating the rule and supporting a site-specific standard for Keetac.

“Nothing outlined in that letter prevents the MPCA from revisiting their flawed standard — the letter simply states the MPCA previously failed to follow the Clean Water Act when they tried to update the standard in the past,” Emmer wrote to Iron Range Today. “The letter does not prevent the MPCA from revisiting the standard.”

****

Minorca Mine idled for six months in 2009, the only time it ever stopped production for economic reasons since mining began in 1977. Earlier this year, it was fully idled as Cleveland-Cliffs was losing money and ore stockpiles overflowed.

Pumps were pulled from the pits, an action Arbogast had never seen throughout all the industry downturns he’s endured unless it was permanent. The pooling water visible along the roadside is a sure sign this idle will extend much longer than six months — possibly for good — he said.

Minorca Mine produced the most expensive pellet on the Iron Range, more than Northshore Mining where Cliffs once idled production over a mineral royalties dispute. Keetac, by comparison, is among the lowest cost mines per ton in North America.

“That’s what the administration, both the governor’s office and the MPCA, don’t get,” Arbogast said. “I’ve watched these company guys over the last 30 years, and a couple, three, four bucks a ton — they just lose their s**t. Like they’re going to get fired.”

The MPCA, when considering U.S. Steel’s variance, looked at the profitability of the company and not operating costs. It said U.S. Steel had between $384 million and $2.524 billion in profit per year, and could remain profitable as a whole to comply.

U.S. Steel was sold to Japan’s Nippon Steel earlier this year, and part of the sale agreement with U.S. regulators called for $14 billion in total investment across the U.S. Steel footprint. That included $800 million in Minnesota.

Nippon reported more than $4 billion of profit in 2024, which was not factored into the MPCA’s review, but is present in public perception of Keetac affording environmental regulations.

Maccabee said the capitalist system of U.S. economics should play a role in compliance. Once the government sets the rules, the companies find the lowest cost option to meet regulations, and that’s that.

“The problem I have is that political pressure, ginned up by the companies in many cases, interfered with a proper working of the system,” she said

MPCA experts have acknowledged the cost to implement reverse osmosis is high, and there’s limited data to show if the only known treatment method significantly supports higher wild rice volumes. The agency’s cost analysis for U.S. Steel said reverse osmosis implementation would add $17.50 per ton to pellets leaving Keetac’s facilities.

Industry and union officials say the per-ton increase threaten to make the plant’s pellets noncompetitive on the open market. Bartovich compares it to how companies approach “Buy American” or green initiatives on products.

“Everyone wants a deal,” she said, and in the steel business the easy bargain to hunt is in the price of iron units.

Steelmakers in the south can import some products from Brazil, for example, at a cheaper rate. Nippon recently bought into an iron ore operation in Canada. Domestic iron units provide an advantage on the competition, but tariffs are only cost-prohibitive when importing is less economical.

A number of companies in and beyond the mining industry have opted to do businesses elsewhere. Talon Metals moved the processing side of its prospective copper mine in Tamarack to North Dakota. Scranton Holding also vetted Minnesota’s neighboring state for operations in 2024.

“People get focused on the wrong thing and the focus goes to capital expenses,” Bartovich said. “It’s operating expenses that worry me. Increases from other areas go into operating expenses, and when you tack all those on, you can’t afford to operate in the state of Minnesota.”

****

Where the Range fits into the global pellet hierarchy isn’t something it’s reckoned with in the past. It built a name mining the iron that made the steel necessary for American troops to defeat the Axis powers in World War II.

Globalization contributed to mine closures and lost jobs in the 1950s and 1980s, but to an extent, Iron Range mines have been insulated through domestic contracts and integration within the companies. Those factors still exist. Cleveland-Cliffs keeps its pellets in house. Same with U.S. Steel, but it also sells on the open market.

Newer ore bodies in Australia and Guinea call back to the early days of the Range. There’s higher grade ore right on the surface level, meaning production costs to mine it, process it and import it are significantly lower.

Maccabee, when reviewing the 2024 Fraser survey, said she didn’t realize the industry only considered Minnesota a place of moderate mineral potential, with relatively low-quality ore by global comparison.

“We are still stuck in a time warp when he had some of the best iron mines, ” she said. “If we have our current quality of mineral potential — and if it’s not sufficient enough to sustain the cost of doing it in a clean, safe and modern way — then other states have more minerals. They have a higher mineral potential.”

Peltier said what sometimes gets lost in the history and heritage of Iron Range mining is the sheer size of the global steel landscape. The region relies on the industry, and it’s a big part of the state, but Range mines aren’t as critical to supply chains as they were in the World War II era.

“The more questions people ask about where we fit in the global supply chain, the better,” he said. “The better we understand it, the better decisions that we’ll make locally, the better information that we’ll have. That will help set the stage for how we process information around what is happening to us and with us.”

****

All these factors — the costs, the permits, the standard, the sale and the closures at Cliffs — come at a tenuous point in time. While U.S. Steel didn’t show evidence that adding reverse osmosis costs would “cause a slowdown or shutdown at Keetac,” according to the MPCA, the landscape has changed as it so often does.

It’s true that under Nippon ownership, Keetac is exposed to larger profit margins from the parent company. So is the fact the age-old fight of pitting corporate interests against working class jobs is also at play here. But the Range has long succumbed to understanding the power of a boardroom, and how it can turn off the lights at will.

There’s some restraints on Nippon as part of its purchase agreement with the U.S. government, which has seen the Trump administration already exercise its “golden share.” Still, there’s relatively uncreative ways for the company to test those boundaries.

Closing Granite City Works in Illinois prior to June 2027, or other production locations like Keetac before June 2035, is disallowed under normal circumstances. Temporarily idling a facility before those deadlines, however, is allowed under standard practice.

A temporary idle was how Cliffs described its outlook for Minorca, which plays a role in the greater concern. If Minorca can indefinitely close under a temporary idle status, so too can Keetac.

Even as an active mine, there’s questions abound.

U.S. Steel shifted its Fairfield, Alabama facility from a blast furnace operation to an electric-arc furnace, rendering Keetac’s regular pellet obsolete there. Should Granite City Works close in 2027, the mine would lose another blast furnace it feeds into. The DRI facility at Keetac has operated for less than 30 days in the two years since it opened, despite its capacity to produce 4.5 million tons of pellets annually.

“Other than that, Keetac really doesn’t have a purpose anymore,” Arbogast said. “This place could turn into an Aurora-Hoyt Lakes ghost town, with a Dollar General and a gas station, just like that. People don’t get it. ‘Oh, the mines will be here forever.’ The f**k they will.”

****

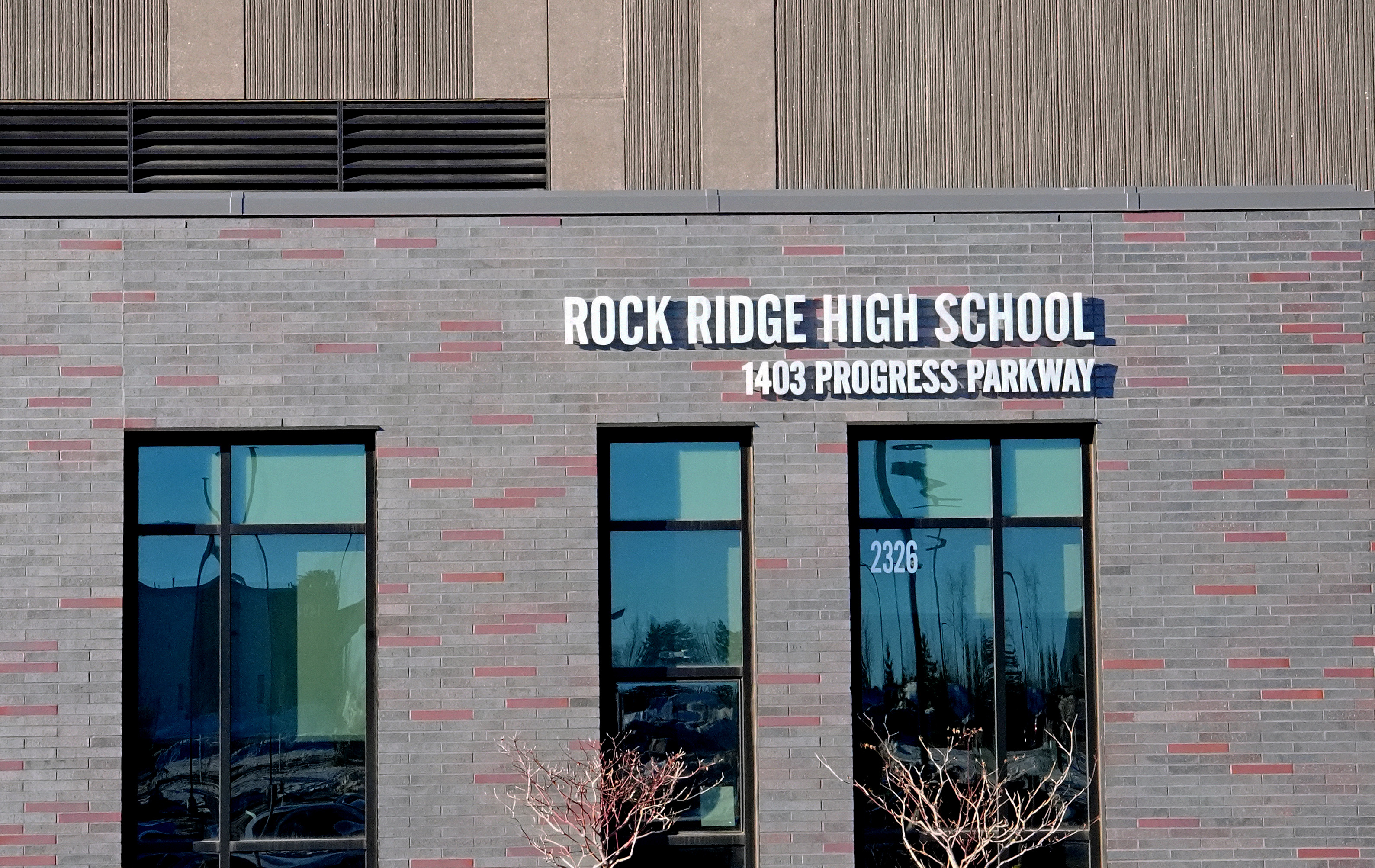

A sign entering Keewatin greets oncoming traffic with its name laid across an outline of Minnesota. Just below it, another notes the city is home to Keetac mine, a testament to the humble and unassuming nature of this spot on the map. It’s an industry town with fewer than 1,000 people, proud of their blue collar lifestyle, but wary of its grip on them.

The mining town dynamic is one Cliff Tobey knows well.

He’s been associated with Keetac for more than 20 years. A union president for USW Local 2660 in another lifetime. Between 2008 and 2022, the city watched Keetac gain local notoriety every downturn as the first mine to close and the last to reopen.

Tobey headed Local 2660 in December 2016 when Keetac ended a 20-month idle period, finally easing local distress that it would remain closed.

When he started at the mine in 2002 under National Steel, it went bankrupt and was purchased by U.S. Steel the next year. The latter outcome spared this West Range community from a less desirable fate, but not before National Steel’s failure wreaked havoc.

“I watched employees, some just a few weeks from retirement, forced to work years longer to recover part of the pensions they were about to collect,” Tobey said. “Retirees, including my father, lost their health insurance overnight. My mother was battling lung cancer and breast cancer at the time, and my dad’s monthly health insurance jumped from $100 to $1,600.”

Keetac is now at the center of attention, and if the worst fears of its future prove to be founded, the city will bear the brunt as the usual trickle down effect takes hold.

To this point the sulfate standard has been a mining issue — Keetac, Minntac and down the line — but communities on the Iron Range face a double-sided cost of compliance through mining operations and municipal wastewater systems.

“My concern is that this will decimate the Iron Range, and then they’ll go, ‘Whoa, we can’t have this happen everywhere else,’” Bartovich said, “and then it’ll get changed.”

Peltier said too much of the sulfate standard has been viewed specifically as a Greater Minnesota or Iron Range issue. The broader impact hasn’t been realized in communities and industries across the state and metro region.

“This will land everywhere,” he added.

MPCA notes that it considers public sector variances differently from its profit-focused approach for private companies. It cites affordability rates for residents, and wastewater treatment rate increases must be less than 2% of the median household income.

The agency says a monthly rate increase higher than $92 per month, in a community with an average income of $55,000 a year, is too high for residents of the municipality to take on without a variance.

For reference, the median household income across the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation district is $66,595 a year as of 2023, according to Census data compiled through Minnesota Compass. The combined average income for Hennepin and Ramsey counties is $88,671 a year.

Even if a variance is granted to a community or company, it only extends the timeline for treatment and doesn’t hand out a hall pass to avoid compliance. Either way, Peltier said, cities are facing an unknown line item on a future budget.

“No one has done a credible study of what it will cost all of the municipalities that would have to be a part of this,” he said. “The cost of compliance is currently unknown for municipalities, and that in itself is scary.”

Maccabee pointed to her time as a city councilor in St. Paul when a routine sewer separation was approved. The city asked taxpayers to take part in it, and that cut of the cost ended up covered by state and federal funds.

“In some cases, especially when you’re dealing with public entities like small towns, there may be a need for state tax relief,” she said. “The thing is, the worst possible system is to have inconsistent enforcement of regulations, where no one knows what to do and the mature remediation industry cannot develop.”

****

MPCA had 60 days to decide on the Keetac variance request — an Oct. 3 date that expired as this past weekend arrived — but U.S. Steel has agreed to a four-month extension to allow the agency an opportunity to review and respond to more than 1,100 comments.

Discussion on the draft permits, site-specific standards and the entirety of the issue are expected to continue during that time, which ends in February just before the Legislature convenes.

Meanwhile, in communities like Virginia and Keewatin, the snapshots of daily life will continue.

They won’t betray what’s on the surface. People commute to work as school buses move along their routes. The bars, restaurants and stores are visited with relative frequency. Life goes on. That’s what has to happen.

A number of workers from Minorca and Hibbing Taconite will stick it out. Others will consider leaving for new opportunities. Some already left the Iron Range in the past.

Those like Arbogast will continue the fight. A USW grievance officer early in his career, that’s how he knows to support his union and this place. Maccabee and Water Legacy will keep their efforts ongoing, too.

So will the communities, because so much right now rides on the mining industry. So many relationships and families built around mining families. So much below the surface of those snapshots.

“They have a vested interest in the infrastructure of local communities and that the steel industry provides the backbone jobs for people that pay property taxes, people that shop locally, people that have kids and send them to school — they’re employed at mines and other places too,” Peltier said. “It’s not a ‘your problem’ situation, it’s an ‘our problem’ situation.”

This story was updated at 1:30 p.m. to replace a quote and better explain the context of the intended comments.