What is the cost of losing a culture? And what is the cost of trying to reconnect it with the world?

These are questions many Iron Rangers will never have to answer. Not in our lifetimes. Maybe for generations. After the last load of iron ore is scooped from the ground, the open pits will be forever implanted in the landscape. They will tell the Iron Range story like the red dirt beneath the feet of descendants we may never meet. But what will happen to our culture if such a huge part of our identity, mining, is taken away?

Culture can shift or fade over time like a natural process. The stories passed down are what we leave behind to preserve it. There is certainty in how the heritage of this place will be remembered; records and artifacts neatly in order. Still, history has a way of drawing stark contrasts.

In 1978-79, Iron Range mines set modern records for employment and shipment levels. Herb Brooks would lead the Golden Gophers men’s hockey team to a third straight national championship. The North Stars selected Bobby Smith, a future all-star and rookie of the year, first overall in the NHL draft.

By comparison, in August 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed onto a law protecting the religious and cultural freedoms of Indigenous people for the first time. That was only 47 years ago. The heritage of the Ojibwe, driven underground and allowed to be erased, had already lost generations.

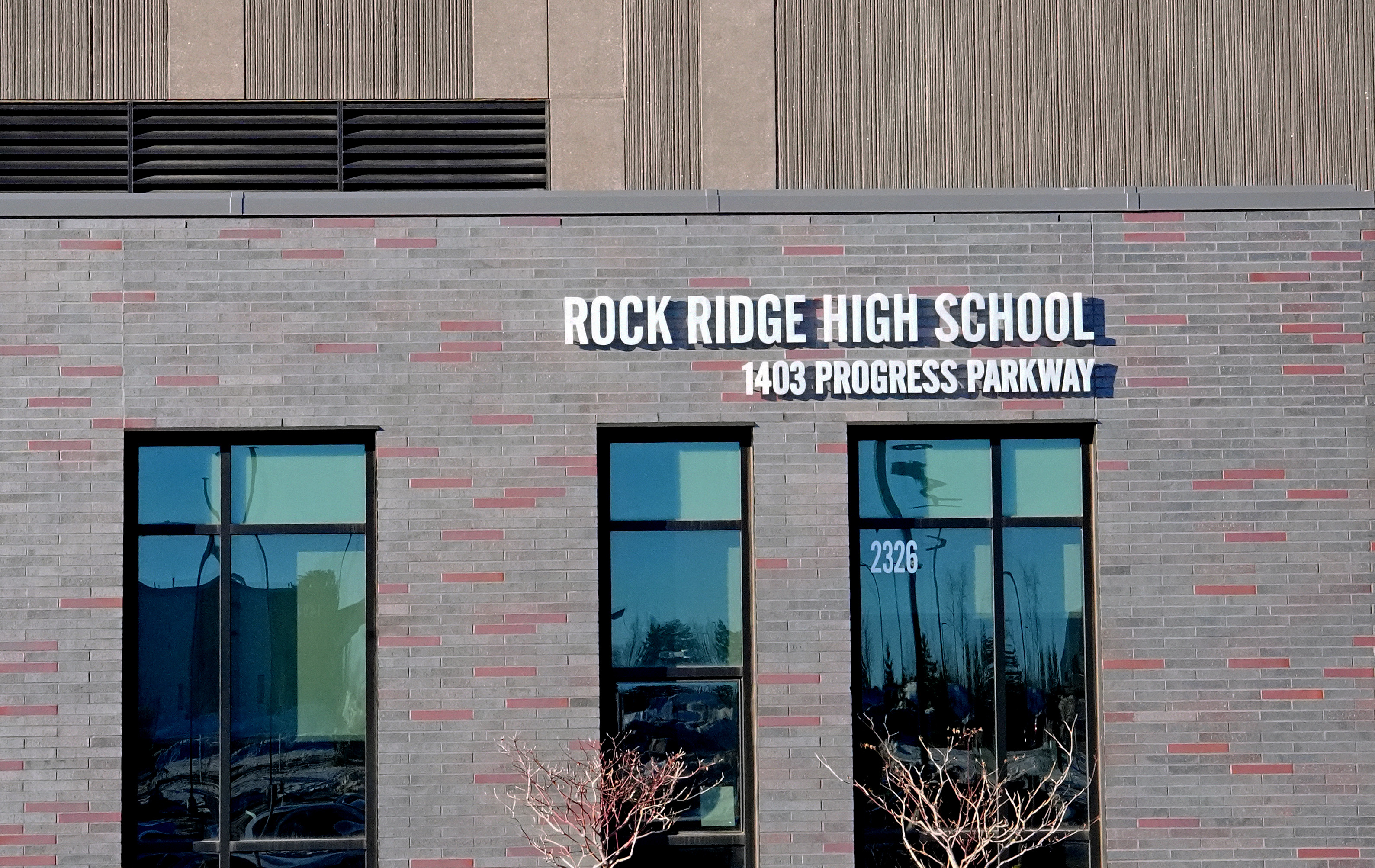

Meredith Two Crow is standing behind the Rock Ridge bench overlooking center ice, thinking about the history about to unfold. Her regalia’s colors jump out against the glimmering white of the frozen rink. The metallic jingles ring in sync with every movement.

She was at-risk of being among the lost. Her mom was 18 years old in 1978. A generation raised in the shadows.

Tonight there is excitement building. Nerves. It will be the first-ever high school hockey game broadcast in the Ojibwe language. Two Crow and about a dozen other Ojibwe people will dance to the beat of the drum circle pregame. Her daughter is out there, too. She’s 11 years old. Two generations removed from those shadows, shining a light on their culture.

“It’s amazing the connections that can come together when something like this wants to be,” Two Crow says. “Breaking down barriers, because that’s what it is. We’re channeling through oppression. Our language and our ways and our culture weren’t even allowed, when you think about it, not that long ago.”

There is a cost to sharing a culture once suppressed to something short of extinction, but past nonexistence. A conflict between sharing its beauty and pride, and risking exposure to the stereotypes and caricatures. Two Crow felt that pull as the game came closer to reality. She heard from tribal members. These are for us. These are our values.

What is the cost of a lost culture unsure it wants to be found?

She remembers high school. It was not so long ago. Native people were dirty, poor and drunks. So went the tropes. She knows her daughter and other Ojibwe boys and girls face the same stigmas. The same barriers to speaking their own language. She thinks about her cousin, a fierce advocate for the Indigenous culture denied to a generation before them.

Sharing who she is as an Indigenous woman can make a difference. It can return respect to her people and their ways. It can start here.

“I think it’s just so important when we get into rooms that make us feel uncomfortable, those are the rooms where you do need to continue to speak out and continue to be who you are and continue to show up regardless of how you feel, because that’s where the change starts,” she says. “I have to keep telling myself that, because sometimes I get really overwhelmed.”

Two Crow did not want to be the face of a historical moment. Not for Rock Ridge High School. Not for Minnesota hockey. Not for the Ojibwe. In ways, not even for herself. Yet, here she is.

That conflict is also within her as she talks about it. Her people have been hurt before. What stops us from being hurt more? Especially now, on the precipice of this moment. When their culture takes center stage with the Iron Range’s long, storied hockey heritage.

Anticipation takes over the tunnel leading onto the ice. There’s no turning back now. A sea of colors, feathers and jingles. Rock Ridge is following in the footsteps of the Minnesota Wild in broadcasting the game, but taking it up a notch. Two songs. Two dances. Center ice. People will hear and see the Ojibwe language and culture like they never have before.

“This is big for the Indigenous community,” said Maria Poderzay, director of Indigenous Education at Rock Ridge. She will watch from the tunnel with an ear-to-ear smile. This is the right moment.

Still, the conflict of it remains on the surface.

Elders in the crowd and drum circle were alive in 1978 when the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) was passed by Congress. To that point, U.S. policy focused on assimilation and not coexistence between tribal and Western cultures. Indigenous people saw their religion and ceremonies banned, their language quieted, families separated, names changed and boarding schools created to make them part of Christian society.

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation to free Confederate slaves in 1863. More than 100 years later, Black people in the U.S. were still segregated to different schools and water fountains. The 1964 Civil Rights Act didn’t flip the switch on discrimination, and AIRFA didn’t bring a sweeping re-emergence of the Indigenous culture. Distrust of the government saying their ceremonies were now allowed, no longer forced underground, remained. It still does today.

Ojibwe culture survived because families took risks to keep their heritage alive. It had to survive. To keep its ways. To bring another generation along. To stay relevant among its own people.

Now, they are just putting it out there. On full display. For the Iron Range to see. For Minnesota to see. For the nation and world to see. A YouTube link away from connecting to a culture that is apprehensive to be seen.

The impact of historical suppression lingers. Two Crow says she now takes accountability for not being fluent in her own language. The truth is, few her age know Ojibwe the same as English. Revitalization efforts extended only so far. There’s still rebuilding to do.

“We may have been lost,” Two Crow says. “People can call us that, but when we show up in places like this, society remembers who we are and what was taken from us. I think that plays a crucial role in trying to identify as being Indigenous. I just spent 30 years of my life not trying in my culture, but now I’m here showing up.”

Crossing through Eveleth on Grant Avenue will take you by the world’s largest free-standing hockey stick. At 110-feet tall, it towers over an oversized puck, mural and statues of Iron Range hockey legends John Mariucci and Frank Brimsek.

Blocks over is the Hippodrome, the famed high school hockey arena where John Mayasich led Eveleth to four consecutive Minnesota state high school championships. Along the highway is the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame. The 1980 Olympics “Miracle on Ice” gold medal team, which had a line composed entirely of Iron Rangers, is immortalized there.

A Mountain Iron kid named Matt Niskanen played for Virginia/MI-B in high school and brought home the Stanley Cup in 2018 as a top-6 defenseman for the Washington Capitals. He retired in 2020 and now coaches the Rock Ridge boys team.

Hockey is embedded in the genetics here. Kids are laced up in skates as soon as they are able and slid onto the ice. They go through youth hockey programs that run year-long, at least for those able and driven enough to add to its history. Forget March Madness, state hockey tournaments and the NCAA Frozen Four have their own office bracket pools.

There are Indigenous roots in the game of hockey, stemming from the Mi’kmaw people in eastern Canada. The game, Oochamkunutk, was played on frozen rivers and lakes. The Ojibwe played Baaga’adowewin, a stick and ball game often associated with lacrosse but holds similarities to hockey.

What is the cost of living in a culture? There are barriers to participating in one’s heritage. Becoming a part of legacy. Joining another.

“I know a lot of Indigenous people that don’t have the means to get to and from a job,” Two Crow says. “It’s a slippery slope.”

Being on the ice or behind the bench is a familiar spot for her. She directs the dancers where to enter the rink, and that despite the rugs, the freshly Zamboni’d ice will be wet underneath. Two Crow is part of the generational hockey families on the Range. Her 11-year-old daughter, Aniyah, is in her third year playing for Rock Ridge. Two Crow played for six years with the Ely Timberwolves. Her cousins played hockey. Her brother. As long as she can remember there was a family member putting a stick to ice.

As she went through hockey programs in her youth, there was often just one other Native family in the program. Sports, especially hockey, are investments for families. Commitments of time and finances that stretch thin already overburdened lower-income households.

“I think as a kid, you want to always play a sport and be involved, until it’s beaten out of you so many times from being told no,” Two Crow says. “I used to think, as a kid, they must just not want to.”

The risk of using hockey as a vehicle to reach people with the Ojibwe culture is rooted there. So few Indigenous children can connect to the hockey culture of the region. She has watched this story play out with her generation. Her daughter’s. Money for helmets and skates is a luxury. Consistent rides to practices from adults are scarce. So much of the skill necessary to just play is honed in those early ages.

This dynamic is not exclusive to sports or hockey for many Indigenous families. Those working, providing and staying out of the trappings of stereotypes can find limits to participating in their own culture. They might attend ceremonies, hunt, gather, set nets. There is something to connect with, but some parts are just out of reach.

“I’m going to just keep it real,” Two Crow says. “If you don’t have the money to do it, even on the reservation, there’s a lot of families that can’t be a part of the pow-wow circle because their family doesn’t have the means to create, design or pay an artist to make an outfit for them.”

Regalia are expensive and time-consuming. There is a cost to their culture now, which she blames on Western influence. The extravagance of the outfits outweighs locally-sourced materials. There is quality, then there is quality, and the latter has become the expectation.

“I think things like that aren’t spoken about enough to have adequate change, because part of it is filled with shame,” she adds.

Storytelling is deeply-rooted in Ojibwe to pass down the teachings of their culture. Traditionally, aadizookewin or the sacred stories, are only told during the winter when snow blankets the ground and the lakes are frozen. A show of respect to the sleeping spirits contained in them.

The story of the wolverine, Gwingwa’aage, tells of one spirit who would fly on the outer edges of Mother Earth, daring to get closer each time. His three brothers warned this particular troublemaker about being too careless, and on one flight, he was pulled into the Earth. He crash-landed, creating a crater that filled into a lake.

Years later, a wolverine emerged from the lake, snarling and surly toward the people and animals surrounding it. The people would recognize the brazenness of the sky spirit who crashed into Earth years ago, giving him the name Gwingwa’aage, or the one that came from a shooting star.

If there is a connection between Gwingwa’aage and Two Crow, it is their boldness to push the boundaries. If we don’t share our culture, how will people respect us? Her cousin, Dani Pieratos, provides her strength. She believed in Indigenous ways, but found connection with people outside the tribe. Outside her comfort zone. People from different ethnicities that wanted to support the Ojibwe culture.

Two Crow admits she used to be close-minded about her Indigenous heritage. If you aren’t brown, why are you in the circle? But Dani changed her outlook. Native blood and ancestral ties transcend physical features. This turnabout connects Two Crow to the story of the Rock Ridge Wolverines. A school and mascot born out of collaboration. Communities that set aside parochial differences for a common good.

It all led to this point. Two Crow is president of the Rock Ridge American Indian Parent Advisory Committee (AIPAC), which connected her to Poderzay, AIPAC Vice President Jenny Markwardt and others. The school’s Indigenous Education team landed a Language Revitalization Grant from the Minnesota Department of Education. They hired Alexander Hayes, an Ojibwe language teacher at Rock Ridge. They wanted to do more.

Then the Minnesota Wild broadcast a game in the Ojibwe language. When Paul Gregersen at Cultures, Humanities and Arts on the Iron Range (CHAIR) floated the idea, we can do this here at Rock Ridge, the doors opened up. Together they formed sponsors, engaged the school and connected deeper with the regional Indigenous Education leaders.

“This is a positive project with a far reach, that builds bridges across our state during a time when Minnesota needs it most,” Gregersen said. “From Fond du Lac and Cloquet, through the Range and Bois Forte, Grand Rapids and Leech Lake.”

Something special was happening. Something was also missing. Dani, the guiding force for Two Crow’s connection to her Ojibwe heritage, committed suicide last year. She would be here helping. Without a doubt. Two Crow will carry on her activism through these games. Through something historical.

The dances and songs are over now. Two Crow exits the ice and walks down the tunnel. Halfway through and the moment hits her. She jumps up and down. Hands in the air. We did it. She embraces Poderzay, who has tears in her eyes, through a screaming, celebratory hug.

Somewhere above them, the Ojibwe broadcast team is at work. The Rock Ridge and Cloquet girls teams are on the ice. History is unfolding. A click away from hearing their language describe a game that is practically religion here. The dancers and drummers instead walk into the lobby and perform one more song. This was never about hockey. Not completely. This is what it was about. Their culture. Brought to life in a way unique to them.

“If we are talking about revitalization of language and culture, it’s from every single one of us,” Two Crow says. “Once I realized how many different tribes’ blood are in me … I used to think it was lost, because there are so many different languages that I have in me, so many different cultures … I just hope that the Indigenous kids of Rock Ridge can see that we are still trying.”

What is the cost of losing a culture?

Meredith Two Crow stands on the ice. She takes a moment. Closes her eyes. Native songs and drums overtake the arena. She soaks it in. The insecurity of this night melts away. She thinks of Dani. Her mother. Her daughter. Of the Indigenous Rock Ridge girls who shied away from recognition.

The Ojibwe culture is alive tonight. Right now.

It was never lost. Just scared. Traumatized from its people being killed for speaking their language, or jailed for singing their songs. Tonight, it was out in the open.

What is the cost of trying to reconnect it with the world?

Mino-bimaadiziwin, the good life, Two Crow says. Taking a past filled with hurt and hate, and filling it with love, bravery and humility. She cannot change the past, or rewrite the history books. There is still much of their real story to tell. The future to her is as much about the Seven Grandfather Teachings as it is the seven generations to come.

It is sharing the powerful ceremonies of her culture. The drum, and all of its power and healing. The storytelling. The language. It is about breaking the stigma. The one she faced in high school. The stereotypes alive today.

A hockey game alone is not going to revitalize the Ojibwe way of life. It will not wipe away generations of oppression, or change the way many people see Indigenous culture. On the night AIPAC and CHAIR presented the game’s details to the Rock Ridge School Board, two members voted to keep Columbus Day a school holiday. Hurdles remain. But the culture was seen tonight. Through the lens of how the Ojibwe see themselves. Without the distortion of appropriations.

The cost of reconnecting with the world is hope. Hope that others will rediscover their culture. Hope that their ways can finally thrive again. For something more than acceptance.

“The only thing that we can try to improve is the future for the future generations,” Two Crow says. “I feel like we’re always at this in-between with Indigenous cultures and the Western world. I know it’s never going to coincide. I know that. But even if we just look for that happy medium where both worlds can exist.”

More Photos

Watch the broadcast

Miss the Ojibwe broadcast of the game by Maajiigoneyaash Jourdain. Check it out through the Rock Ridge YouTube channel.